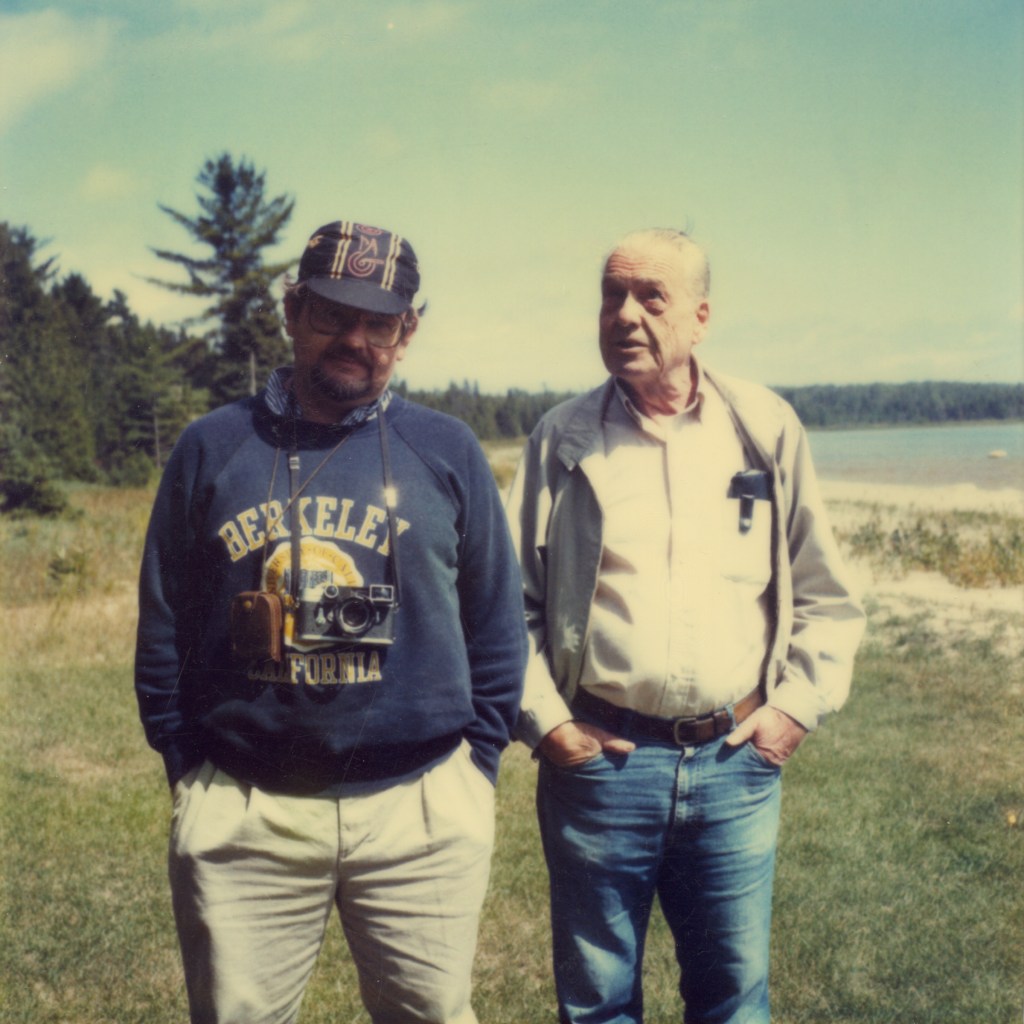

(Tony and Wendell Galt, 1980s. Photo likely taken by Janice Galt. I can imagine the photos I’d want to illustrate this essay, but I don’t have them.)

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court by Mark Twain is a book I’ve thought about a lot over the years. The main character travels back in time to King Arthur’s court and proceeds to reconstruct a then modern Nineteenth Century technological society, defeats Merlin, and gets the girl. The plot hinges on the Yankee—Hank Morgan—being an ingenious engineer who is fully capable of recreating the modern marvels of the Victorian Age in the distant past. Most of us, I suspect, would fall short of that standard. We would be pretty useless if we were suddenly transported in time back to 7th century England. Twain’s novel, published in 1889, was written in an era where a technically adept and educated person could plausibly have a working knowledge of ALL of the technology of the time. You see this in a lot of the speculative fiction of the nineteenth century: protagonists—invariably male—who have a degree of mastery over an astonishing variety of scientific and technical disciplines. Think Professor Otto Lidenbrock, the hero of Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth, or “The Traveller” in H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine. To some degree, this is part of the romantic allure of steampunk—the idea that with a little tinkering, a single mind could be capable of manifesting a veritable smörgâsbord of tech. In the first centuries of the Industrial Revolution there was, or at least there seemed to be, some truth to this. Benjamin Franklin invented bifocals AND lightning rods. Thomas Edison invented the lightbulb AND the phonograph—or at least that was the legend.* These men were to the Industrial Age what Da Vinci was to the Renaissance. So when did this era end?

I think that my grandpa (whom I’ve mentioned here), was a member of the last generation that was capable of comprehending most of the technology they used. Not only did he understand it, but he could repair it or even build it. He believed in doing what he could for himself. I never really had a conversation with him about it—he died when I was in my mid-20s, well before my handy householder phase—but I’ve come to think this ethic was connected to his modernist architectural practice. He’d been educated at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in the late 1930s, where Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer of the Bauhaus found refuge after fleeing Hitler. While Gropius never succeeded in replicating the Bauhaus’ craft-based curriculum at Harvard, the focus remained on pragmatic problem solving, design, and humanistic philosophy. There was a crafty, human scale to modernism that you see in the buildings and furniture these architects built for themselves. This was Wendell through and through and I don’t know where else he would have picked up this mindset. Certainly not as a child raised by missionaries in China in the 1910s and 20s.

His house in Woodland Hills—a suburb of Los Angeles—contained, in miniature, all of the major industries of its time. The electronics bench was in the den, the woods and metals workshop in the garage, the darkroom in the guest bedroom (next to his architectural drafting table), and the makeshift foundry where he cast aluminum parts was behind the garden shed. He was a loyal subscriber to Popular Mechanics and Popular Science magazines. At the time these miraculous periodicals (seriously, check out the link) contained detailed instructions for projects as disparate as fixing clogged drains and building small airplanes. His house was filled with furniture he’d built, stereo equipment he’d soldered together, photographic prints from his darkroom, and more. Short of making his own cathode ray tubes, there was little he couldn’t do. Either he’d made it himself or it was built in such a way that a reasonably knowledgeable and motivated person could service it themself. Short of the electronics, I don’t doubt that he could have replicated much of the technology he used if sent back to medieval England.

While my dad had benefited from some of this early training, the world he came to occupy became more complicated. VCRs, personal computers, LED clocks… forget it. Electronic components were miniaturized on cheaply assembled circuit boards that weren’t meant to be repaired. While he was handier than many of my friends’ dads—he repaired our bicycles and made some basic furniture—he never achieved the kind of comprehensive mastery Wendell did. And me? I’ve designed and made some furniture, but I’m hopeless when it comes to electronics, coding, and repairing finicky mechanical things. I’m happy to take agency over some of the material aspects of our lives, but there’s only so much I can do. My attempts to fix electronics have pretty much ended in disaster. If there’s a tiny screw, I will drop it. Raspberry Pi? More like raspberry pie. And these screens we stare into? I don’t have the slightest idea how they work. For most of us, a smartphone might as well be magic. Our material world is no longer fully comprehendible and I can’t help but think that that’s at the root of many problems. It’s something that’s led us further down the path of consumerism.

The Sustainability Angle

There’s a sustainability angle to this, there always is…. What do you do when you need a thing? Where do you begin? Wirecutter.com? Google? The things that are presented to fill your need, how will you get them? Amazon? Best Buy? What will they made from? Where will they have been manufactured? The consumerist way of approaching problems always seems to lead to the kind of consumerist solutions that led our society to the edge. There are too many people who aren’t aware that there are alternatives.

Being a maker of things changes how your value them… for their grace, their utility, and their construction.

My grandpa would have started with graph paper, a mechanical pencil, and his scrap heap. If he didn’t have what he needed, he would have gone to the hardware store to pick up a few things. If he couldn’t build it himself he’d consider buying something. He was a lifetime subscriber to Consumer Reports and he aimed to get the best made thing he could afford so that he’d never need to buy it a second time. In those days, that was possible. But his consumer choices were always informed by having direct knowledge of how things are designed and made. He was a craftsman before he was a consumer. This helped him to understand what was worth buying. Because being a maker of things changes how your value them… for their grace, their utility, and their construction. You’re quick to find the weak points, to see the faults.

Too often sustainability has been framed as adopting a different and better set of consumer choices. And sure, there’s an aspect of that that’s true. But in fact, the entire consumerist ethos needs to be discarded. We don’t need to be able to reproduce our technological society in order to think like makers. Even if much of the technology we use on a daily basis has moved beyond our comprehension, you can still make a foot stool out of 1″x6″s, a saw, and a hammer. Every little step you take will begin to change your relationship to consumer culture. And I believe that’s something we all need to do.

* Edison began appearing as a literary character in science fiction, under his own name or lightly disguised, during his lifetime. John Clute and Peter Nicholls refer to these works as “Edisonade” in their Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. The 1898 book, Edison’s Conquest of Mars by Garrett P. Serviss is a particularly interesting sounding specimen. Most ‘boy inventor’ stories derive from this, Tom Swift being the best known example. Imagine speculative fiction with Elon Musk as a main character… Wait, does that exist? I refuse to check.

Leave a comment